As the race between MT and human translators intensifies, to maintain their competitive advantage when translating technical material, now more than ever, human translators need to provide translations which have accurate terminology and read idiomatically. Even a sophisticated translation engine still can’t do it. To show you this, I used a well-known neural machine translation (NMT) engine, available online, to translate four paragraphs from an Infinitum Electric article a few months old on axial-flux motors. (Axial-flux motors are widely used in several applications, including electric vehicles and HVAC systems.) What follows is the NMT of each paragraph, together with the issues found, and my corrections and remarks. Please note that the backtranslations of my renderings are not suggestions on how the English should have been written. They are intended only to convey the meaning of what my Italian is saying. (If you find the article too technical, just jump to the Conclusion.)

1) The heart of any electric motor consists of a rotor that revolves around a stationary part, called a stator. The stator, traditionally made of iron, tends to be heavy. Stator iron accounts for about two-thirds of the weight of a conventional motor. To lighten the stator, some people proposed making it out of a printed circuit board.

NMT:

Il cuore di ogni motore elettrico è costituito da un rotore che ruota attorno a una parte fissa, chiamata statore. Lo statore, tradizionalmente realizzato in ferro, tende a essere pesante. Il ferro dello statore rappresenta circa due terzi del peso di un motore convenzionale. Per alleggerire lo statore, alcuni hanno proposto di ricavarlo da un circuito stampato.

Human Translation:

Il cuore di ogni motore elettrico è costituito da un rotore che ruota attorno a una parte fissa, chiamata statore. Quest’ultimo, tradizionalmente fabbricato con lamierini in ferro, tende a essere pesante. Il ferro dello statore rappresenta circa due terzi del peso di un motore convenzionale. Per alleggerire lo statore, è stato proposto di realizzarlo con un circuito stampato.

Issues with NMT:

1a) “…chiamata statore. Lo statore, tradizionalmente realizzato in ferro…”

Idiomatic as well as technically correct Italian:

“…chiamata statore. Quest’ultimo, tradizionalmente fabbricato con lamierini in ferro…”

Remarks:

- Italian has a dislike for repetitions at a close distance, as in “statore. Lo statore…”, thus we replace the second occurrence of “statore’ with “quest’ultimo” (“this last one”) which is a common device used for such purpose.

- Yes, the stator is made of iron, but in Italian is better to write, more accurately, of sheets of iron, thus “lamierini in ferro” rather than simply “ferro”.

1b) “…alcuni hanno proposto…”

Idiomatic Italian:

“… è stato proposto…” (…“it has been proposed…”). In cases like this, Italian prefers a passive structure, leaving out of the equation who could be the “same people” (“alcuni”) who made this proposal.

1c) “…di ricavarlo da un circuito stampato…”

Idiomatic as well as technically correct Italian:

“di realizzarlo con un circuito stampato”

Remarks:

“di ricavarlo” means making the stator from a printed circuit board through a certain process, while the article makes clear that the stator itself will be a printed circuit board. And since to replace “ricavarlo” we have used “realizzarlo”… we have replaced “realizzato” in the first line with “fabbricato”, again to avoid a repetition.

2) Although the idea of replacing a hunk of iron with a lightweight, ultrathin, easy-to-make, long-lasting PCB was attractive from the outset, it didn’t gain widespread adoption in its earliest applications inside lawn equipment and wind turbines a little over a decade ago. Now, though, the PCB stator is getting a new lease on life. Expect it to save weight and thus energy in just about everything that uses electricity to impart motive force.

NMT:

Sebbene l’idea di sostituire un pezzo di ferro con un PCB leggero, ultrasottile, facile da realizzare e di lunga durata sia stata allettante fin dall’inizio, non è stata adottata su larga scala nelle sue prime applicazioni all’interno di macchine per il giardinaggio e turbine eoliche, poco più di un decennio fa. Ora, però, lo statore a circuiti stampati sta per avere una nuova vita. Ci si aspetta che risparmi peso e quindi energia in quasi tutto ciò che utilizza l’elettricità per imprimere forza motrice.

Human Translation:

Sebbene l’idea di sostituire un pezzo di ferro con una PCB leggera, ultrasottile, facile da realizzare e di lunga durata sia stata allettante fin dall’inizio, non è stata adottata su larga scala nelle sue prime applicazioni all’interno di macchine per il giardinaggio e turbine eoliche, poco più di un decennio fa. Ora, però, si aprono nuovi orizzonti allo statore a circuiti stampati. Ci si aspetta che riduca il peso e quindi il consumo energetico in quasi tutto ciò che utilizza l’energia elettrica per imprimere forza motrice.

Issues with NMT:

2a) “…con un PCB leggero…”

Technically and grammatically correct Italian:

“…con una PCB leggera…”

Remarks:

“PCB” stands for “Printed Circuit Board” (“scheda di circuiti stampati”) and nouns in Italian have a gender. This requires to adapt the adjective “leggero” (“lightweight”) to its referent “scheda” (“board”) which is female, thus “leggera.”

2b) “…[lo statore a circuiti stampati] sta per avere una nuova vita…”

Idiomatic Italian:

“…[lo statore a circuiti stampati] sta rinascendo” or “…si aprono nuovi orizzonti allo statore a circuiti stampati”

Remarks:

Even though the NMT of the figure of speech “getting a new lease on life” is not totally botched, we can make it sound more natural shortening it (“sta rinascendo”) or we could even reorganize the sentence (“…new horizons open up for the PCB stator”).

2c) “…che risparmi peso e quindi energia in quasi tutto ciò che utilizza l’elettricità per imprimere forza motrice”

Idiomatic as well as technically correct Italian:

“…che riduca il peso e quindi il consumo energetico in quasi tutto ciò che utilizza l’energia elettrica per imprimere forza motrice” OR “…che faccia risparmiare il peso e quindi energia…”.

Remarks:

The concept here is that a PCB stator would be lighter and thus every application where is used would be lighter and would use less energy. The original translation doesn’t convey these concepts. And “elettricità” for “electricity” is a colloquial term but here we want an accurate term. In a technical article you would use the equivalent of “power”, that is, “energia elettrica”.

3) This saving of energy is critically important: Software may be eating the world, but electricity is increasingly what makes the world go round. Electric motors consume a little over half of the world’s electricity today. Some 800 million motors are now sold annually worldwide, according to the market research group Imarc, a number that has been increasing by 10 percent each year.

NMT:

Questo risparmio di energia è di importanza critica: il software può anche mangiare il mondo, ma l’elettricità è sempre più ciò che fa girare il mondo. I motori elettrici consumano oggi poco più della metà dell’elettricità mondiale. Secondo il gruppo di ricerca di mercato Imarc, ogni anno vengono venduti circa 800 milioni di motori, un numero che è aumentato del 10% ogni anno.

Human Translation:

Questo risparmio di energia è di importanza critica: è possibile che il software stia ‘mangiando il mondo’, ma l’energia elettrica è sempre più ciò che lo fa girare. I motori elettrici consumano oggi poco più della metà dell’energia elettrica mondiale. Secondo il gruppo di ricerca di mercato Imarc, l’anno scorso sono stati venduti circa 800 milioni di motori, con un tasso annuale del 10%.

Issues with NMT:

3a) “…il software può anche mangiare il mondo, ma l’elettricità è sempre più ciò che fa girare il mondo.”

Idiomatic Italian: “…è possibile che il software stia ‘mangiando il mondo’, ma l’energia elettrica è sempre più ciò che lo fa girare.”.

Remarks:

The English, of course, refers to the prophetic article “Why Software is Eating the World” written by Marc Andreessen on the WSJ in 2011 on the dramatic and broad technological and economic shift in which software companies would take over large swathes of the economy. An accurate translation of the article title would have been “Perché il software sta avendo effetti dirompenti nel mondo” (“Why Software is Disrupting the World”). The statement by Marc Andreessen was translated literally in Italian by everyone since it’s so pregnant––but always between quotes because the literal translation it’s quite unclear to a common Italian reader. In fact, it’s always followed immediately by an explanation. So it’s ok to use the literal translation, but you need to slightly rephrase it and put it in quotes to make it sound natural.

Also, in idiomatic Italian we want to avoid to repeat twice “il mondo”, so we write “…che lo fa girare” where the pronoun “lo” identifies “il mondo”.

“…elettricità …” (twice!)

Technically correct Italian: “…energia elettrica…”.

(Repetita iuvant: in a technical article you always want to use accurate terms.)

3b) “…ogni anno vengono venduti in tutto il mondo circa 800 milioni di motori, un numero che è aumentato del 10% ogni anno”

Accurate Italian: “…l’anno scorso sono stati venduti circa 800 milioni di motori, con un tasso annuale del 10%…”.

Remarks:

Here we need to do some sleuthing. The English says that every year 800 million motors are sold worldwide and that this number has been increasing by 10% each year, but this statement needs to be articulated in Italian. (As an aside, the NMT missed completely “worldwide”, “in tutto il mondo”.) To understand better, we go to read the original market research, which states that the global motor market reached a volume of around 546 million units in 2017, growing at a CAGR of more than 10% during 2010-2017. Doing the math starting from 2017, we arrive at 799 million units sold in 2021. Thus the complete meaning is “…approximately 800 million motors were sold last year, with an annual growth rate of 10%…”. Here we have a case where we need to reinterpret the English to provide the appropriate translation. Of course it’s good practice to always flag to the client a problematic piece of text, as in this case. (The client will appreciate it.)

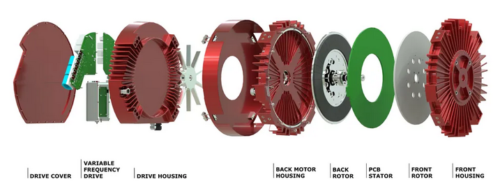

4) An axial-flux motor is a design in which the stator’s electromagnetic wiring stands parallel to a disk-shaped rotor containing permanent magnets. When alternating current flows through, it makes the rotor spin. The motor also has an air core—that is, there is no iron to mediate the magnetic flux and nothing in between the motor’s magnetic parts but thin air. Put all these things together and the result is an air-core axial-flux permanent-magnet motor.

NMT:

Un motore a flusso assiale è un progetto in cui il cablaggio elettromagnetico dello statore è parallelo a un rotore a forma di disco contenente magneti permanenti. Il passaggio della corrente alternata fa girare il rotore. Il motore ha anche un nucleo d’aria, cioè non c’è ferro a mediare il flusso magnetico e tra le parti magnetiche del motore non c’è altro che aria sottile. Se si mettono insieme tutti questi elementi, si ottiene un motore a magneti permanenti a flusso assiale con nucleo d’aria.

Human Translation:

Un motore a flusso assiale è realizzato in modo che gli avvolgimenti statorici siano paralleli a un rotore a forma di disco contenente magneti permanenti. Il passaggio della corrente alternata fa girare il rotore. Il motore è anche dotato di un nucleo d’aria, per cui non c’è materiale ferromagnetico che generi il flusso magnetico e tra le parti magnetiche del motore non c’è altro che un sottile traferro. La macchina così ottenuta è un motore a magneti permanenti a flusso assiale con nucleo d’aria.

Issues with NMT:

4a) “Un motore a flusso assiale è un progetto in cui il cablaggio elettromagnetico dello statore è parallelo a un rotore a forma di disco contenente magneti permanenti”

Idiomatic as well as technically correct Italian:

“Un motore a flusso assiale è realizzato in modo che gli avvolgimenti statorici siano paralleli a un rotore a forma di disco contenente magneti permanenti”.

Remarks:

“…è un progetto…” is a literal translation of “is a design…” which doesn’t sound natural in Italian, so we rewrite it as “…è realizzato in modo” (“is made in such way”).

4b) “…il cablaggio elettromagnetico dello statore …”

Technically correct Italian: “…gli avvolgimenti statorici…”.

Remarks:

That’s the only correct way to say in Italian “[stator’s] electromagnetic wiring”. If, instead of “wiring”, the English term had been “windings”, any translation engine would have find the correct translation “avvolgimenti” in its bilingual dictionary or corpus of translations. If instead the translator has expertise in the field where they are translating, bumping into a slightly different term in the English is not a problem.

4c) “Il motore ha anche un nucleo d’aria, cioè non c’è ferro a mediare il flusso magnetico e tra le parti magnetiche del motore non c’è altro che aria sottile”

Technically correct Italian: “Il motore è anche dotato di un nucleo d’aria, per cui non c’è materiale ferromagnetico che causi un flusso magnetico e tra le parti magnetiche del motore non c’è altro che un sottile traferro”.

Remarks:

Both “materiale ferromagnetico” and “ traferro” are the accurate terms to use in this context for “iron” and “thin air” rather than “ferro” and “aria sottile”. And “mediare” is a literal translation of “mediate” which distorts the meaning of the source text, which is “to bring about” (“causare”).

4d) “Se si mettono insieme tutti questi elementi, si ottiene un motore a magneti permanenti a flusso assiale con nucleo d’aria.”

Idiomatic Italian: “La macchina così ottenuta è un motore a magneti permanenti a flusso assiale con nucleo d’aria”.

Remarks:

“Se si mettono insieme tutti questi elementi, si ottiene…” is a literal, colloquial translation for “Put all these things together and the result is…” which is unsuited to a technical article. The alternative above, “La macchina così ottenuta è…” (“The machine built this way is…”) is just one of the many appropriate possible renderings.

Conclusion

In the above analysis I have highlighted only the less subtle issues I found—thanks for bearing with me while we inched our way through each sentence. I showed you how, even though you can get the gist of technical material with a translation engine, you will not get all the time sentences that sound natural in Italian nor will you avoid terminology inaccuracies. I edited a machine translation (MT) for the first time approximately 30 years ago. The engine output was quite poor at that time. There’s no doubt that progresses have been made in MT, but I am confident that human translators will be able to get better results for a while. You might think: Well, then an easy way to go is to have the NMT engine translate the text and use a human translator to edit the result, that is, to use MTPE (Machine Translation Post Editing). But as you can see from my remarks above, to identify and correct stilted phrases and terminology inaccuracies you need advanced expertise in the field and still, is hard work. First of all, you need to find a translator with the appropriate expertise. Who might not want to do such slog all the time. And anyway, you need to pay them appropriately. In the end, you might end up ahead asking such translator to do the whole job from the start. And bear in mind that I still haven’t tested yet NMT with technical texts much more complex than the article we dealt with here. Stay tuned.